Annotated Bibliography - History of Diagramming

I am exploring the controversy surrounding teaching sentence diagraming in school. It is my opinion that diagraming is a crucial skill for students to learn and assists them in becoming better writers. This argument is documented at least as far back as the 1950s and is polarizing at best, with strong opinions on both sides.

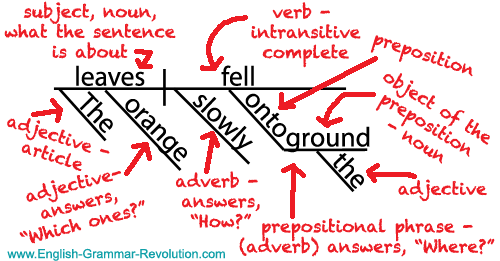

I teach at a small charter classical academy in North Texas where grammar and sentence diagramming are introduced early in lower school and enthusiastically embraced throughout the remainder of a student's years at the school. Studying grammar is studying the building blocks of our language. The ability to diagram sentences allows students to break down grammar into the most simplified form, gaining understanding as both a reader and a writer.

Because this argument stems over at 70 years, I chose to evaluate two articles from the 1950’s in addition to three current pieces. It is interesting to note that the arguments do not seem to have changed in over seven decades, those who support diagraming, have valid, arguable reasons, as do those are in the anti-diagraming camp.

Becker, Z. (1952). Discard Diagraming? The English Journal, 41(6), 319–320. https://doi.org/10.2307/808673

Having read Anthony Tovatt’s (1952) article “Diagraming: A Sterile Skill” in the English Journal, teacher Zelma Becker (1952) investigates questions regarding sentence diagramming including: “Why do we diagram? When did the practice start? Do other countries teach this in school? Why do we cling to diagramming”? (p.319) Becker taught high school English in the 1950s, while she supports the practice, noting that it went back as far as the 1850s when her father was taught to diagram sentences in school, she is still interested in finding out more about the practice.

Becker (1952) surveys other teachers in her school, particularly those who taught foreign language and those who were foreign educated, to find out if this practice was relegated solely to the United States. She determines that no other country taught sentence diagraming as part of grammar education, it is truly an American English language tradition. Foreign language teachers also confirmed that while it was not part of the traditional language, they found diagraming sentences an effective tool to “make clearer some point of usage or grammar”(p.319). Becker feels that there was value in learning the skill and that it provided students with a clearer understanding of structure and grammar (p. 319).

This article, though written in 1952, supports my fervent belief that learning to diagram sentences is crucial to develop students who not only write well, but are also comprehensive readers. Becker, rather tongue in cheek, ends her article with a quote from Tovatt’s (1952) essay, “This finding alone should give the conscientious teacher pause and cause him to re-examine the effectiveness of his teaching practices” (Tovatt as cited in Becker, p. 319). She felt, as do I, that the more I investigate sentence diagraming pros and cons, the more I am certain, it is an effective tool in a grammar teachers toolbox.

Bowden, W. R. (1959). Guilt by Association: The Sentence Diagram. College Composition and Communication, 10(2), p. 89–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/355262

William Bowden (1959) presents a solid argument in favor of conventional sentence diagraming (what we now refer to as the Reed-Kellogg system). Even though he takes a pro-diagraming stance, he did respond to common complaints surrounding the process of diagraming, including that it is too time consuming, that its merely pasting labels on words, and that it “looks scientific, but usually science fiction” (p.90).

Bowden (1959) fields both sides of the argument over sentence diagraming. While he solidly supports conventional sentence diagraming education, he also does a fair job of presenting other diagraming systems and refuting anti-diagraming arguments. He declares the “virtues” of conventional sentence diagraming are that it makes clear characteristic patterns (i.e., Ernest Hemingway’s sentences will look different than Virginia Woolf’s), is a schematic picture of sentence function, and reveals “interrelationship of the structural layers” ( p.90). He introduces readers to other systems of diagraming including those developed by Fries, Francis, Lloyd & Warfel, Roberts, and Burnett. He concludes that conventional diagraming is the “only way to dissect a sentence into its ultimate components without becoming too unwieldly” (p.94).

Sentence diagraming is part of the culture of my school, in some ways it is a rite of passage. Bowden’s article only reinforces my support of teaching this crucial skill to students. I was intrigued by the other systems of diagraming and might investigate those further. This article was written in 1959, yet I wonder if those other systems are still practiced by any grammarians, or if they have disappeared into the history of diagraming.

|

| Previous incarnation of diagramming of W.C Fowler |

Florey, K. (2012, Mar 26). A Picture of Language. The New York Times. https://archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/26/a-picture-of-language/

Kitty Florey (2012) shares a bit of the history of how sentence diagraming came to be. She reports a school master named SW Clark (1864) from Homer NY first shared the concept in his book, A Practical Grammar: In which Words, Phrases, and Sentences Are Classified According to Their Offices and Their Various Relations to One Another. Florey declares the inception of diagraming to be “profoundly innovative, dazzlingly ingenious and rather whimsical idea [of] analyzing sentences by turning them into pictures” ( para. 3 ). She details further innovations in sentence diagraming, closing her article with the age-old question: “Does diagramming sentences teach us anything except how to diagram sentences” (para. 3)?

Florey (2012) is not as thorough as Bowden was in 1959 in her report on the evolution of sentence diagraming, however she does describe life before diagraming, and the wicked archaic process of “parsing”. Clark likens diagraming, Florey reports, “making the abstract rules of language into pictures was like using maps in a geography book or graphs in geometry” (para. 5). Clarks diagrams used cumbersome balloon-like frames in his diagraming, in 1877 teachers Alonzo Reed and Brainerd Kellogg shared their concept of sentence diagraming based on Clarks, using lines instead of bubbles, creating the Reed-Kellogg system we use today.

This article may have been my favorite. I enjoyed learning the history of our conventional sentence diagramming. I will use this information as “fun facts” in class whilst teaching students this vital skill.

Frances, S. (2012). Grammar Literacy: How Vampires, Potlucks, and Diagrams created an Affective Learning Community. Literacy Link, 3. https://resourcespacec.svsu.edu/mount/library/archives/public/LiteracyLink/documents/LL2012F.pdf#page=3

Dr. Sherrin Francis (2012), Assistant professor of English at a community college in Texas, shares her approach to helping students transcend their fears of grammar and instead embrace it. She noticed that her incoming freshman students could write required essays and papers, however they lacked basic grammar knowledge to write them well.

Dr. Francis (2012), recognizing the need to reach students and help them learn the tools of grammar, including sentence diagraming, she created and sponsored The Hard-Core Grammar Club, which she based on four pieces of research which point to the importance of a social connection, personal connection, food, and multiple means of engagement in the success of students. She promoted the club as “for students with a passion for, curiosity toward, or even just a healthy fear of grammar and language” (p.4). The club met bi-weekly and included a pot-luck dinner. Students mingled with each other and learned/reviewed one part of speech or sentence pattern and then they worked together to diagram a series of sentences. The club continued to grow and support students each year.

The idea of creating a grammar club and doing so upon a humorous pretense like going through The Ultimate Handbook of Grammar for the Innocent, the Eager, and the Doomed, a book by Karen E. Gordon (1984), is frankly genius, and a great way to invite students for help they might very well need, while also providing them with built in social structure to support them throughout their remaining time at school. I would love to implement a similar club at my school to reach the students who would benefit from help but are unsure how to ask.

Wilson, B., Chappell, S., Chapman, M., Smith, N., & Nichols, D. (2017). A Primer Diagramming Sentences. Communication: Journalism Education Today, 50(4), 19-22. https://search-ebscohost.com.ezproxy.se.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=123884716&site=ehost-live

Bradley Wilson (2017) reports on a series in The New York times on the craft of writing, which posed the question, “Diagraming sentences: What, after all, is it good for?” (p.19). This prompted him to survey four teachers from across the country, to learn more about their opinion of diagraming and its practice in the classroom. In the article he shares his belief that diagraming helps writers “understand, visually, the function of every part of the sentence,” even likening it to a challenge puzzle like a crossword (p.19).

Among the educators he surveys, the support of diagraming ranges from it plays an important role in seeing “how each word in the sentence fits and what its purpose is in that sentence,” to “it is the wrong approach for teaching good writing” (Wilson 2017, p.20). Three out of four of the educators generally support sentences diagraming as an effective tool toll for writing well.

As I am in support of diagraming, this article furthers that support. As one teacher

interviewed by Wilson (2017) suggests, “take the time to analyze basic sentence structure, and it will pay dividends in the future” p. (19). Wilson closes the article touting multifaceted usefulness of diagraming, “The need to write clearly and present information logically goes on and on – the skill is essential for every profession” (p.22).

Comments

Post a Comment